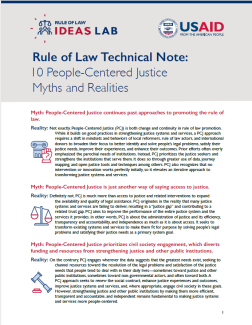

Myth: People-Centered Justice continues past approaches to promoting the rule of law.

Reality: Not exactly. People-Centered Justice (PCJ) is both change and continuity in rule of law promotion. While it builds on good practices in strengthening justice systems and services, a PCJ approach requires a shift in mindsets and behaviors of local reformers, rule of law actors, and international donors to broaden their focus to better identify and solve people’s legal problems, satisfy their justice needs, improve their experiences, and enhance their outcomes. Prior efforts often overly emphasized the parochial needs of institutions. Instead, PCJ prioritizes the justice seekers and strengthens the institutions that serve them. It does so through greater use of data, journey mapping, and open justice tools and techniques among others. PCJ also recognizes that no intervention or innovation works perfectly initially, so it elevates an iterative approach to transforming justice systems and services.

Myth: People-Centered Justice is just another way of saying access to justice.

Reality: Definitely not. PCJ is much more than access to justice and related interventions to expand the availability and quality of legal assistance. PCJ originates in the reality that many justice systems and services are failing to deliver, resulting in a “justice gap” and contributing to a related trust gap. PCJ aims to improve the performance of the entire justice system and the services it provides. In other words, PCJ is about the administration of justice and its efficiency, transparency and accountability, and independence as much as it is about access. It seeks to transform existing systems and services to make them fit for purpose by solving people’s legal problems and satisfying their justice needs as a primary system goal.

Myth: People-Centered Justice prioritizes civil society engagement, which diverts funding and resources from strengthening justice and other public institutions.

Reality: On the contrary, PCJ engages wherever the data suggests that the greatest needs exist, seeking to channel resources toward the resolution of the legal problems and satisfaction of the justice needs that people tend to deal with in their daily lives—sometimes toward justice and other public institutions, sometimes toward non-governmental actors, and often toward both.A PCJ approach seeks to renew the social contract, enhance justice experiences and outcomes, improve justice systems and services, and, where appropriate, engage civil society in these goals. However, strengthening justice and other public institutions by making them more efficient, transparent and accountable, and independent remains fundamental to making justice systems and services more people-centered.

Myth: People-Centered Justice exclusively focuses on technology to improve user experience as well as access to court and legal services.

Reality: That is an oversimplification.Technology can be an integral part of PCJ approaches, but not just to improve the efficiency of existing court and legal services. In PCJ programming, technology can empower people outside of the halls of justice to claim or vindicate their rights themselves. More often, however, PCJ uses non-tech solutions to simplify what is overly complicated using legal navigators, user-friendly forms, and plain language legal documents, including contracts. Using techniques and processes like legal design thinking and human-centered design, PCJ better meets people “where they are” and equips them to solve their legal problems and justice needs with both tech and non-tech tools.

Myth: People-Centered Justice is only oriented toward formal justice systems and services.

Reality: Not exactly. PCJ finds justice solutions that put people at the center of systems and services by working with both formal and informal institutions, actors, and processes.A core PCJ goal is to multiply the means and pathways by which people can solve their legal problems and satisfy their justice needs.

Solutions may be achieved through informal and customary justice systems, alternative dispute resolution processes, or even technology platforms. Solving problems is not the sole province of formal courts or lawyers, but can be achieved with more affordable and accessible community justice options, online portals, and a host of other informal means.

Myth: People-Centered Justice is a one-size-fits-all approach.

Reality: Certainly not.A PCJ approach is driven by the specific legal problems and justice needs of the individual or community in question. It seeks to understand these problems and needs, as well as the current services being offered and how effective they are, before responding. PCJ efforts can prevent as well as remedy, offering diverse justice seekers and populations more accessible, user friendly, and problem-solving assistance that addresses their legal problems (including criminal, civil, and administrative).They pilot new solutions and invest in data to better understand what people need when they seek justice, how they seek to resolve their legal problems, and the obstacles and costs they face along the way.

Myth: People-Centered Justice does not focus enough on gender, diversity, or vulnerable populations.

Reality: Not true.The premise of PCJ is that justice ought to be available to everyone, not just the rich or powerful few.The rallying cry of PCJ and ultimately its goal is “Justice for All,” as set forth in Sustainable Development Goal 16. Effective PCJ programming collects and analyzes data to understand gender and social norms and how women and girls, men and boys, and gender diverse individuals are differently impacted on their justice journeys. PCJ approaches address gender and other social inequalities, needs, and barriers to help close the justice gap and facilitate more inclusive, equal, and equitable systems and services. PCJ enables human creativity to flourish by empowering people in all their diversity, underserved communities, and vulnerable populations to know, use, and shape the law.

Myth: People-Centered Justice is a rule of law approach with no cross-sectoral application.

Reality: Not quite. PCJ is not only a rule of law approach. It also addresses complex development challenges in health care, livelihoods, education, housing, and the environment. Legal problems can lead to health problems, such as depression or substance abuse. Health problems can engender legal problems, such as rising debt and bankruptcy.The social determinants common to those likely to come in contact with the criminal justice system are the same as those likely to engender poor health outcomes. PCJ offers a new and more effective means of cross-sectoral integration to create more resilient individuals, households, communities, and countries. For instance, PCJ approaches can include facilitating medical-legal partnerships or mobilizing educators and faith leaders to serve as “navigators” through complex legal, housing, health, and other processes.

Myth: People-Centered Justice is any form of assistance that considers people's problems and needs.

Reality: Not true.While considering people's legal problems and justice needs is a critical first step toward following a PCJ approach, more is required. Once legal problems and justice needs have been identified through the collection and analysis of data, justice institutions and actors must also collect evidence regarding feasible solutions to design user-friendly responses that are prevention-oriented and solution-driven, then provide justice seekers with multiple pathways to addressing these problems and needs.What makes an intervention people-centered is the emphasis on engaging people, identifying and solving their legal problems, and improving their experiences and outcomes within the justice system.

Myth: People-Centered Justice entails a human rights-based approach (HRBA) to rule of law programming.

Reality: Not really.An HRBA is grounded in the architecture of human rights principles of participation, accountability, non-discrimination and equality, empowerment, and legality. It aims to hold “duty-bearers” to their obligations and support “rights holders” to know and claim their rights. However, PCJ is not per se about rights, duties, or obligations. It is about meeting people’s legal problems and satisfying their justice needs that occur in the context of modern, legally regulated societies and how to resolve them when the justice system and its services are unavailable or unaffordable. PCJ aims to transform justice systems and services from a complex web of rules often administered by overly formalistic and legalistic professionals to one that puts the justice seeker at the center and that is data driven, user-friendly, problem-solving, prevention-oriented, and pathway-multiplying.