BACKGROUND

Disability and Human Diversity: Framing Disability in USAID’s Work

As recognized in the CRPD, “disability is an evolving concept … [that] results from the interaction between persons with impairments14 and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”15 This understanding of disability as a social construct is a departure from traditional framings of disability.

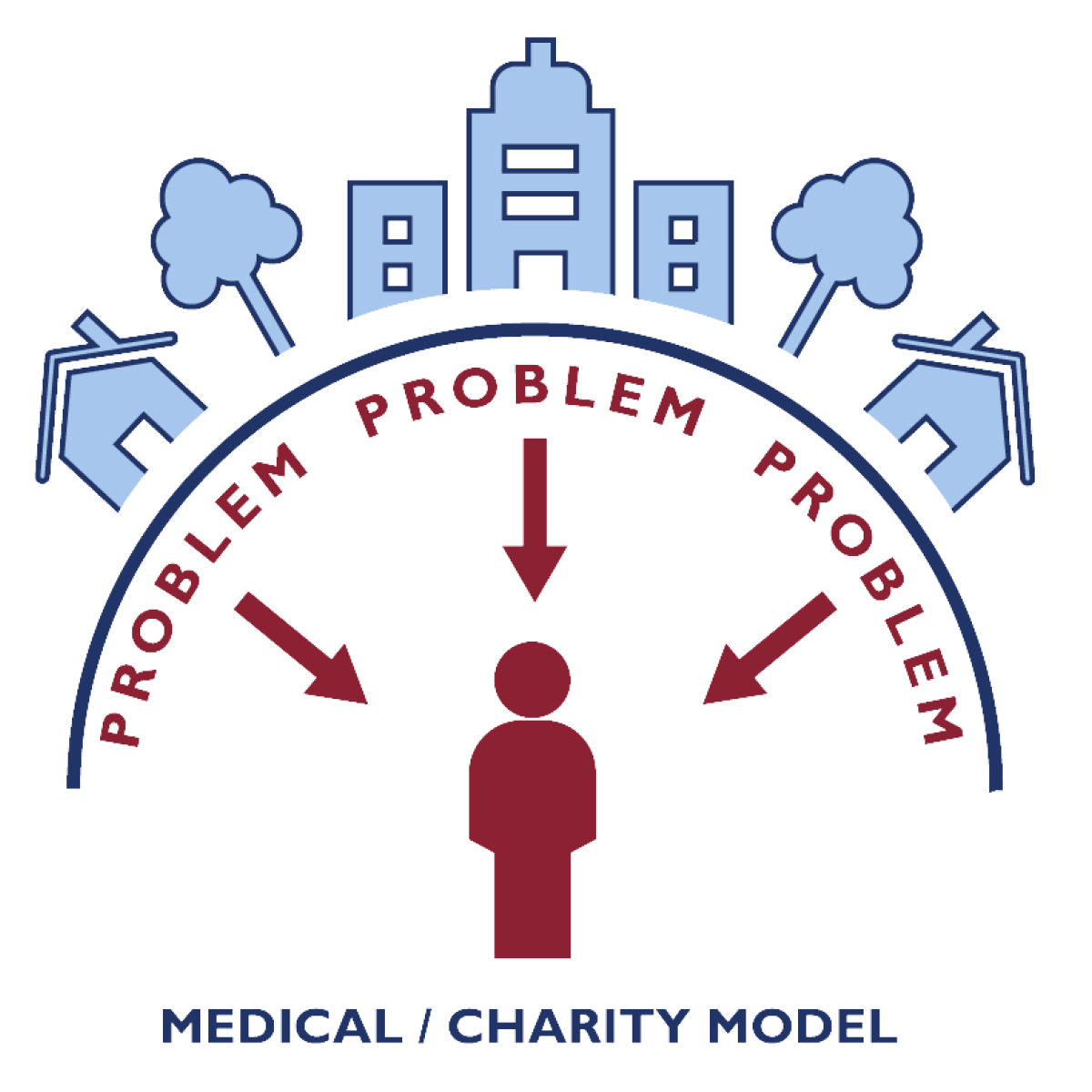

Historically, society has acknowledged that persons with disabilities have experienced problems, but the cause of those problems has often been misattributed to persons with disabilities and has centered on misperceptions of persons with disabilities as deficient.16 These traditional framings have, through time, come to be captured in what are often referred to by disability rights advocates and academics as the “Medical Model” and “Charity Model” of disability. In the Medical Model of disability, society has often sought to “cure” people, regardless of whether this could be achieved or not, and whether they wanted this or not. Such approaches have often encouraged—or forced—persons with disabilities into institutions or to use medicines, surgery, or other interventions to change their bodies or minds to become closer to the prevalent societal view of what is considered “normal” or “typical,” regardless of what persons with disabilities might want or aspire to.

In the Charity Model of disability, often well-intentioned people have tried to offer support, including access to disability- specific goods or services. However, typical delivery models of charity have often adopted unsustainable approaches that disempowered, pitied, or patronized persons with disabilities, deprived them of autonomy and agency, made them dependent upon others, or fostered segregation rather than meaningful and comprehensive community inclusion.

Access to high-quality medical care is as important to persons with disabilities as it is to their non-disabled peers. Charities can have a useful role to play—especially when their work is guided by persons with disabilities. However, by focusing on changing persons with disabilities rather than systems of inequality and discrimination, these two models of disability have frequently subjected persons with disabilities to harm and human rights violations. Furthermore, these approaches have typically failed to successfully address the root causes of persons with disabilities being denied full access and inclusion in society on an equitable basis with others.

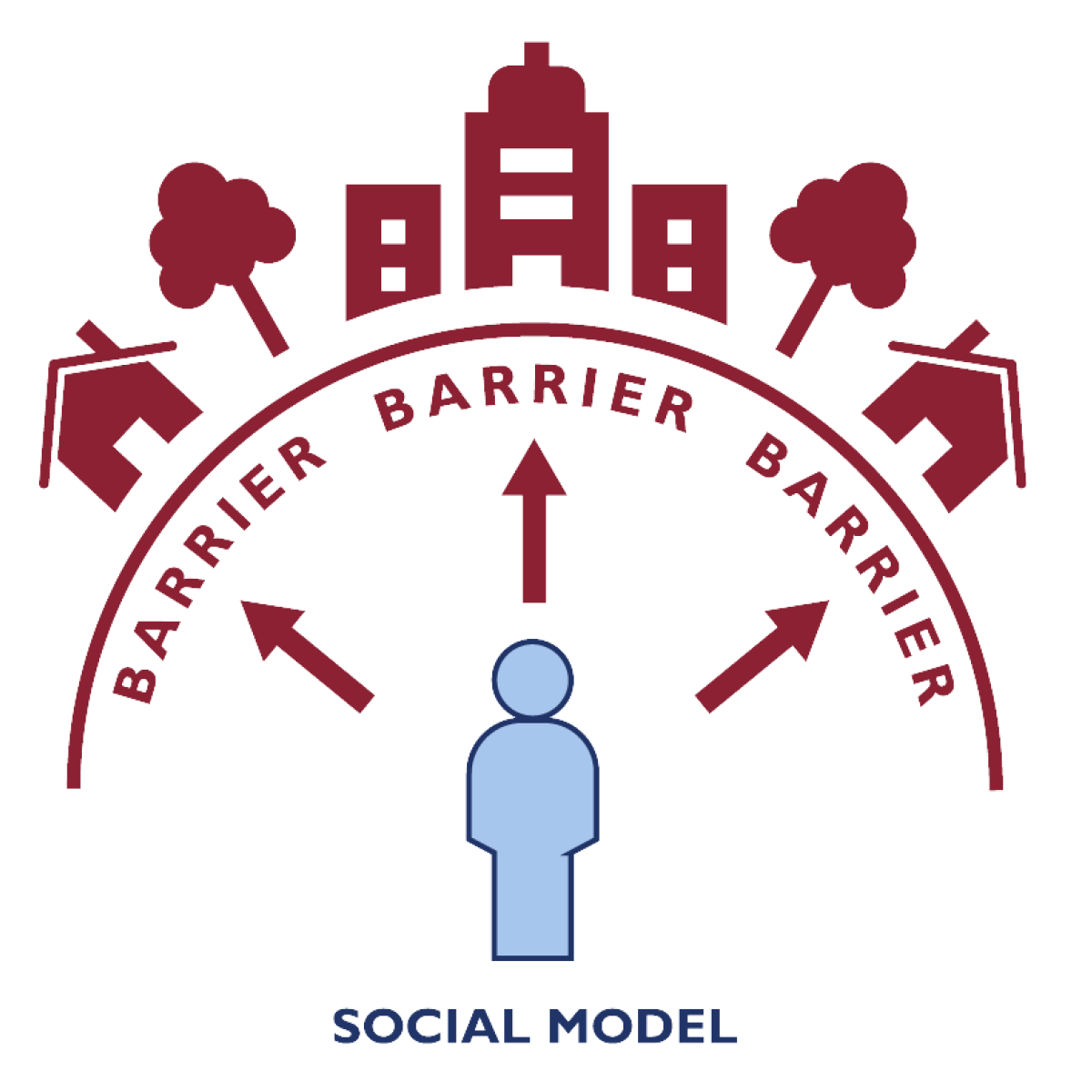

The “Social Model” of disability is a reaction to these traditional framings. Instead of pointing to the person to change, the Social Model looks outward, to society. Under the Social Model, disability is the result of the negative interaction that can occur when people with certain functional conditions or “impairments” encounter barriers in society. Barriers can include physical, legislative, technological, and attitudinal and involve communication, information, and policy.17 The Social Model identifies barriers in society—not persons with disabilities—as the problem.18

USAID references the Social Model to frame a foundational understanding of disability as a social construct resulting from the negative interaction between persons with certain functional conditions and barriers in society. This is not intended to negate other important concepts of disability (such as disability as a political or social identity19), and it should complement what is often referred to as a “Human Rights Model” of disability. A human rights perspective can advance understanding of the negative impacts of the barriers identified by the Social Model’s framing of disability and can inform development approaches that further human rights of persons with disabilities. The Human Rights Model also embraces respect for difference and acceptance of persons with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity20 as well as the proactive provision of equitable supports, in addition to removal of societal barriers, to ensure persons with disabilities are fully included in society and enjoy human rights on an equitable basis with others.21

Situating USAID’s work within the Social Model of disability compels us to focus development interventions on addressing societal barriers to access, equality, equity, and meaningful inclusion for persons with disabilities. The types of societal barriers typically experienced by persons with disabilities align well with the wide array of substantive areas in which USAID works and provide opportunities for the Agency to contribute to the effective removal of such barriers. At the same time, the Social Model’s respect for the individuality, agency, and autonomy of persons with disabilities is consistent with USAID’s commitment to an approach anchored in the protection and promotion of human rights to address inequalities and injustices that hinder development and empower individuals to claim their rights.

DISABILITY INCLUSION IN ACTION

USAID’s “Global Labor Program – Inclusive Futures” (GLP-IF) activity aims to increase the inclusion and confidence of persons with disabilities, particularly women, so they are able to collectively bargain and improve labor rights at the Kenyan companies of global drinks brands Diageo’s East Africa Breweries Ltd . (EABL) and Coca-Cola Beverages Africa (CCBA) . Working with EABL, the program facilitates efforts of smallholder farmers who grow sorghum to organize collectively into hubs . Through the hubs, farmers with and without disabilities gain improved access to agricultural advice, farm inputs, and collective bargaining power to secure higher prices from EABL for their produce . GLP-IF works with CCBA to make its retail distribution chain more inclusive .

The activity provides skills training and support to female retailers with disabilities to grow their businesses and supports them to organize into groups, giving them a platform to discuss common issues and negotiate better margins from CCBA product sales.

“The Global Labor Program has helped me a lot. I have received training on things like recordkeeping and customer service, which have made me more organized. The weekly coaching sessions have also helped me to know what I need to improve on and enabled me to navigate challenges I experience, which have in turn improved my business.” —Josephine, a CCBA retailer who owns a small retail business in Nairobi and is deaf

Persons with disabilities include but are not limited to persons with physical, psychosocial/mental, intellectual, cognitive, sensory, and other disabilities of varying degrees and complexity.22 People may be born with their disabilities or acquire them later due to accident, illness, age, violence, natural disaster, or other causes. Two people may have the same disability, but that does not mean their experiences, disability- related needs, or accessibility requirements will be the same. It is important that USAID’s work encompass persons with disabilities across all disability types; from all backgrounds, sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions, and sex characteristics (SOGIESC); and at all ages and stages across the human life course. An individual’s disabilities may not be readily apparent, and because of the prevalence of disability-based discrimination and stigma, not all persons with disabilities may choose to self-identify as persons with disabilities. For example, some individuals may view themselves as persons with disabilities but may not feel safe or comfortable self-disclosing this to others. Others may not identify as members of the disability community at all, in some cases because of lack of access to assessment services or supports. For some persons, disability is an important aspect of their identity and a source of pride. USAID respects whether and how persons with disabilities self-identify or disclose. The Agency strives to foster safe and respectful environments in which persons with disabilities can feel comfortable in embracing and disclosing that identity as and when they choose.23

Persons with disabilities are not a monolithic group; they are part of every other population and group. Persons with disabilities may also experience the effects of multiple forms of discrimination. This Policy’s intersectional approach recognizes that the many elements of identity, in combination with systems of inequality, can create unique power dynamics, effects, and perspectives that affect persons with disabilities’ access to, and experiences of, development and humanitarian assistance interventions. These factors can be particularly powerful in contexts of transition to and from various states of local stability and fragility, peace and conflict, disaster and development, and political, economic, or societal transitions.

Vision, Goal, and Objectives

Vision: USAID envisions peaceful and prosperous societies in which persons with disabilities enjoy human rights, agency, access, influence, and opportunities to pursue their life goals and equitably contribute to and benefit from the Agency’s development, humanitarian, and peacebuilding assistance interventions that engage people across societies, communities, and countries.

Goal: This Disability Policy seeks to empower and elevate the lives of persons with disabilities in partner countries by helping USAID and our partners recognize, respect, value, meaningfully engage, include, and be intentional in supporting persons with disabilities and their representative organizations to benefit equitably from our work as equal partners.

Objectives: In support of this goal, USAID will work toward the following six objectives.

- Foster disability inclusion and respect for disability rights across Agency programming in development, humanitarian, and peacebuilding assistance.

- Respect, empower, and meaningfully engage persons with disabilities—and their representative organizations—across their life course as drivers of development and peace, agents of change, and essential partners in the generation of solutions.

- Identify and dismantle discrimination and barriers to foster accessible, equitable, safe, and inclusive societies in which persons with disabilities and their representative organizations can advocate for and exercise their rights without fear of violence or pressure to assimilate.

- Recognize, respect, and meaningfully engage and partner with the full diversity of persons with disabilities.24

- Advance the knowledge base of effective programming by strengthening disability-inclusive data collection, research, analysis, and learning associated with USAID programming, including with respect to assessing the quality of programming and representation of persons with disabilities.

- Leverage USAID’s leadership and convening power in fostering political will among international, regional, national, and local institutions to implement disability-inclusive principles and practices as well as accountability to persons with disabilities and their representative organizations.

Footnotes

USAID acknowledges that although the term “impairment” is used in the CRPD, it is not one all persons with disabilities are comfortable or self-identify with; they may prefer “condition,” “functional condition,” or other terms. Back to text

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), Preamble (e) (2006). Back to text

Such framings are not universal. At the other end of the spectrum, persons with disabilities have sometimes been viewed as “special,” “heroic,” and even magical in some cultural contexts. Although ostensibly more positive than framings focused on perceived “deficiency,” these approaches can also be inaccurate and inconsistent with how persons with disabilities would prefer to be seen. Such framings can also result in persons with disabilities being kept away from others in society, viewed as dangerous or less worthy, contributing to deprivation of agency and autonomy and further societal segregation of persons with disabilities. In extreme cases, the perception of persons with disabilities as possessing magical characteristics—including but not limited to persons with albinism—has led to persons with disabilities being maimed or killed for their body parts or forced to self-segregate for their safety. Back to text

Examples of such barriers may be physical, such as the absence of a curb cut preventing access by a person with a mobility disability to a pedestrian sidewalk; legislative, such as a law prohibiting persons with disabilities from serving in elected office; technological, such as a banking mobile app that is inaccessible to blind or low-vision persons; or attitudinal, such as an organization that does not even attempt to recruit training participants with disabilities because it assumes they will not gain as much from the training as other participants. Other barriers may involve communication, such as the absence of a qualified (as determined by the deaf community) sign language interpreter to facilitate a deaf person discussing a health concern with a medical professional or the absence of captioning for a similarly situated hard-of- hearing person who does not use sign language; information, such as the lack of plain language instructions to help a person with a cognitive disability understand how to exercise their right to vote; or policy, such as a policy of an employer to hire persons with disabilities to fulfill an employment quota requirement but then have them not work or remain at home to avoid providing reasonable workplace reasonable accommodations. Back to text

The Social Model has benefits beyond persons with disabilities, as its focus on barriers in society can support universal design approaches that have the potential to benefit all persons, regardless of disability status. Back to text

Joshua Thorp, “Does Disability Shape Political Identity?” University of Michigan (2023). Back to text

CRPD, Article 3(d) (General Principles). Back to text

For example, CRPD, Article 19 (“Living Independently and Being Included in the Community”), and references to persons with disabilities accessing “personal assistance necessary to support living and inclusion in the community.” Back to text

This policy is intended to be relevant to persons with all types and degrees of disabilities. The omission of any specific disability within this document is not intended to exclude individuals with those disabilities from the scope of this policy. USAID also acknowledges that not all persons with disabilities will identify with the broad categories of disability referenced in the CRPD and may prefer different categories or terminology. Back to text

For more information on respectful representation of persons with disabilities, including respecting people’s self- identification preferences—whether for person-first, identity-first, other terms, or no self-identification at all—see USAID’s “Disability Communications Tips.” Back to text

Diversity of the community is relevant not only with respect to disability but also in consideration of intersections with race, ethnicity, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, gender expression, sex characteristics, native or Indigenous origin, age, genetic information, generation, culture, religion, belief system, marital status, parental status, socioeconomic status, appearance, language modality and accent, education, geography, nationality, citizenship, migration status, lived experience, job function, personality type, thinking style, and other facets of identity. Back to text

Previous page - Executive Summary and Introduction | Next page - Principles